The double bind of development projects

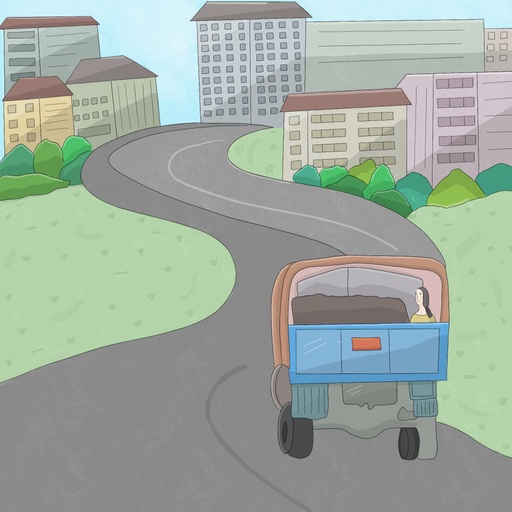

The dynamic development of Yangon has triggered a lot of internal migration, with people moving from one part of the city to another to find work in the new industrial zones and various urban projects. This movement is encouraged when investors need a workforce for their businesses, but families are left uncertain when their plans change. Development projects may mean potential income for the poor, but they also represent their displacement and a continuous fear that their neighborhood might be the next to be evicted.

Buying land that you don’t own

Many people have arrived in Yangon as migrants from rural areas, especially after the devastating cyclone Nargis in 2008. Looking for a secure environment to rebuild their lives, but not being familiar with the complicated procedures of transferring land, many of them have been caught in situations where they bought land from farmers, only to find out that the land belongs to someone else, and that their purchase is not recognized.

Priced out and forced into informality

With the rapid development of Yangon, it is not only migrants that are forced into informality but also long-term residents facing skyrocketing rent prices. Many families are dealing with a shrinking space to find affordable housing, and they have no choice but to move further out to the city’s peripheries. Informal arrangements are often the only choice left to them to have a roof over their head. But these arrangements also imply a lot of precarity, challenges, and the threat of eviction.

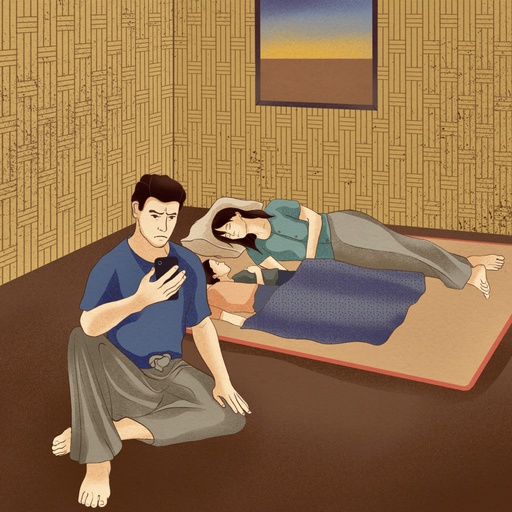

Being invisible in Yangon’s hostels

Hostels are one of the cheapest forms of accommodation for migrant workers—especially newly arrived ones. In Hlaingtharyar alone, there are estimated more than 10,000 of them, most of which operate informally without complying with infrastructure and space requirements. On the flip side, hostels are more flexible for those lacking documents, and they don’t require the typical six-months upfront payment. Many hostel dwellers are not registered to ward or village tract authorities, thus remaining ‘invisible’. Hostels are the last resort for many, despite the cramped and poor conditions they often have.

The impossibility of a stable livelihood

Informal dwellers are blamed for being poor through their own fault; however, the conditions that lead to and keep them in poverty are more often than not related to how systems exclude them and deny them treatment as equal citizens. Displacement adds another layer of challenges to people's already strained livelihood. Relocation without compensation and with no livelihood restoration measures has repeatedly meant that people lose their clients, are further away from their previous jobs, enter unfamiliar markets and face unemployment or reduced income.

Losing vital social networks

One of the consequences of forced evictions is the disruption of people's vital social networks. Particularly in contexts where they cannot access services and resources, they have often had to rely on each other to fill the gaps. These personal connections are so important, for example, to secure a job, look after each other's children, and share the responsibilities of cooking, going to the market, and cleaning their settlement.

Disrupting collective memories

When communities become displaced and lose their connections, it is like a piece of history is being lost. People living in informal settlements each carry the memories and knowledge of how the city has developed and how impactful events have shaped the country as a whole. These collective memories and knowledge are often kept alive through their daily practices and interactions and are at risk of being lost and fading when these communal connections are interrupted.

The vicious circle of poverty and informality

By pushing people further into poverty and making them more vulnerable financially, socially, and emotionally, forced evictions are very far from 'resolving' the issue of slum settlements. Even though the advocates of eviction speak of 'clearance operations', informal settlements don't just vanish into thin air, but they merely find new corners to form from scratch. Many examples in Myanmar and beyond have shown that displacement without adequate measures leads to more informal settlements - and eventually more evictions, as their housing condition becomes a vicious circle.

Standing her ground at all costs

During the past decades, many of Yangon's residents were involuntarily resettled and have had to take roots in unfamiliar parts of the city. Experiencing eviction once is already a traumatizing event, followed by many hardships and sacrifices to make a better living. In the course of the most recent wave of evictions, some find themselves unable to go through it all over again and feel like they have no choice but to stand their ground, even as terror and unbearable circumstances surround them.

The blurry boundaries between ‘formal’ and ‘informal’

When it comes to how people access land and housing, the boundaries between 'formal' and 'informal' can be quite blurry. In numerous cases, people switch from one to the other - in either direction - due to circumstances that are outside of their control and not because they have taken the 'right' or 'wrong' decision. These moves can be so arbitrary and do not follow simple logic; it can be luck or chance. This should be a reminder to not quickly judge and blame squatters as ‘illegal’. The hardships from the coup have intensified such movements and people's insecurity, as Ma Naing's story illustrates.

No one is spared from eviction

It seems that the forced evictions that the junta's soldiers and administrators have been carrying out since 2021 do not spare anyone. Any former tenure agreements are worthless to protect someone, even if their land and housing purchase were made orderly. It doesn't matter who you are, how much you have done for your community, or how well-respected you are among your peers. Only very specific interpersonal connections to a powerful few may be able to secure someone the right to stay in the same spot. Here is the story of a mother whose son is serving in the military and was evicted by the very institution her son belongs to.

"Losing home and business by nationalisation"

Historically, the Myanmar state used urban planning regulations, property transaction regulations, and land and enterprise nationalisation laws to nationalise properties and justify confiscation by the State and military-associated businesses. In addition to urban planning related regulations, the state has used other regulations, targeted against specific groups - such as racialized ethnic and religious groups, ‘potential foreigners’, and political opponents, particularly following 1988 and the 2021 Spring Revolution. Through large-scale nationalisation of enterprises in furtherance of establishing a socialist economy in the 1960s, families lost their homes, properties, businesses and assets.

Resistance from the grassroots people

The revolution that has been sparked since the military coup has activated people from all walks of life, and the poor and working classes play a vital role in the struggles for freedom. Even though they face many limitations, like access to resources and information, urban poor and squatter families from all parts of Yangon have been among the first to fill the streets to protest. And they have been finding ways to show their support and solidarity, even as the military met them with some of the most brutal crackdowns and, later on, with forced evictions. Their role in this revolution needs to be acknowledged and not forgotten, no matter the outcome of the ongoing struggles.